|

There is so much to see in this 1860's ambrotype from the Timely Tresses collection: two well dressed women, a spiffy man, and even a dog. The bonnets in this image are stylistically very different. The woman on the right shows a high brim with narrow sides in the height of popularity in 1863. In contrast, the woman on the left has a rounder earlier bonnet appropriate to the very early 60s or even late 50s. Could this be a younger sister? The fashionable high brimmed bonnet sports two different colored ties, a trend seen in fashion plates, but not often visible on extant bonnets or in photographs.

1 Comment

Due to Covid-19, we have been practically shut down since March. Normally, we get weekly shipments of flowers and ribbons and have a constant flow of changing stock. For the past few months, that has really slowed and I have even had a difficult time sewing millinery feeling that no one would ever wear it. Thank you to those of you who have reached out and supported our business. Fortunately, things have picked up a bit and regular shipments of flowers and other goodies are starting to arrive. Check out our new selections of flowers here.

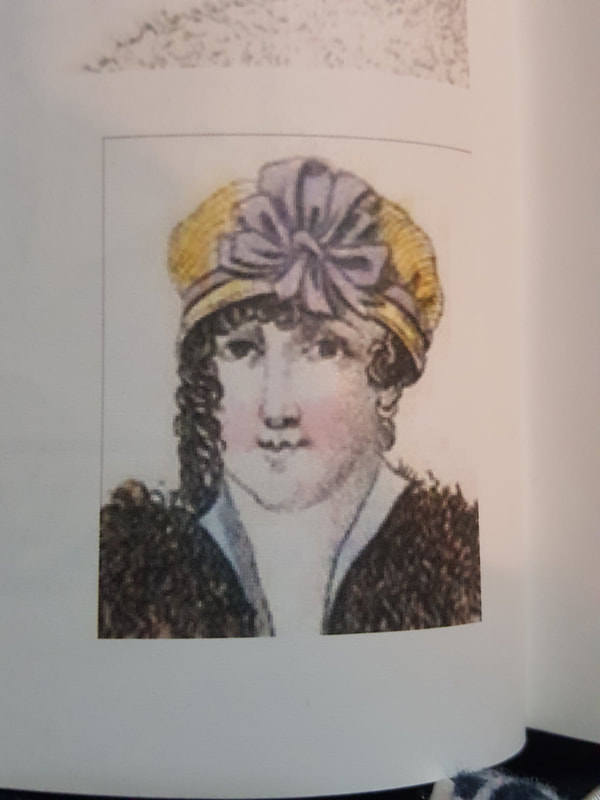

This fashion plate from the late 1830's has many interesting aspects. The men's jackets show both a frock coat appropriate for day wear and a cut away appropriate for more formal occasions. The women's dresses show aspects of the 1830s and the coming 40s. The skirts are wide and short appropriate to the 30s, but the waists are a bit longer and the sleeves are tight indicating the coming trends of the 1840s. The bonnets are still specifically 1830s with very large flared brims.

The Ladies’ Monthly Museum

The Mirror of Fashion October 1819 Morning Dress. A round dress, composed of mull muslin. The body is high; the back full; and the front adorned with work, let in on each side of the bust. The skirt is gored, and finished at the bottom with several small tucks, which are terminated by a flounce of rich scalloped work, set on full. The spenser worn with this dress is composed of ethereal blue gros de Naples; it is tight to the shape; and the waist is of a moderate length; a small pelerine collar falls over; and is very full trimmed with plaitings of net. The long sleeve is of an easy fullness, and is tastefully finished with an epaulette, composed of two rows of shells, of the same material; they are formed by satin rouleaux. Full lace ruff. Head-dress, the Clarence bonnet; we refer to our print for the shape; it is composed of white gros de Naples; the edge of the brim is finished by full fall of lace, surmounted by a plaiting of net; a full plume of ostrich feathers falls over the right side. Blue kid shoes; white gloves; and small French ridicule. Evening Dress. A white lace round dress over a white satin slip. The body is cut very low all round the bust, which is ornamented, in the pelerine style, with falls of lace; the sleeves are composed of net and satin, formed into puffs by small bows of white satin; the lower part is finished by a quilling of net. The skirt is trimmed with three flounces of white satin lace; the two lower ones are surmounted by a very novel and elegant trimming, composed of white satin. The hair is disposed in light curls on each side of the face; the hind hair is dressed in full bows, which are intermixed with roses and convolvuluses. Necklace and ear-rings, pearl. White kid gloves; and white figured-silk shoes. This plate and many others are featured in our fashion plate books. Recently, I have been redoing our fashion plate books for the 1830s. One exciting development in the 1830s is the appearance of American fashion magazines with hand colored plates. Although frequently copied from European magazines, they give us a look at the fashion American editors were sharing with their readers. In the beginning of the 1830s, there are usually only two plates per six month volume and they often do not offer descriptions, This plate is from The Ladies Magazine in May 1833 edited by Sarah Josepha Hale. The Ladies Magazine and The Lady's Book were still two separate entities in 1833, but eventually joined forces to become Godey's Lady's Book.

Good morning everyone! I love cased images. They offer so much detail that every time you look at them you see something new.

The above image is a 1/6 plate ambrotype probably dating between 1856 and 1858. How do I know? The bonnets. Bonnets between 1856 and 1858 were extremely small, sat very low and back on the head. From the front, they look like little halos. In this image, the ties are wide and long. Even when tied, the ends reach to the elbows of the wearers. Some bonnets in the 1850s show shorter ties, but as we move towards the 1860s ties are long. The most important detail to note about the bonnet trimming is the very full cap of netting. If there is any detail reproductions miss, the amount of netting on late 1850s and early 1860s bonnets. If you are trimming a bonnet and wonder if you need more netting, the answer is yes. I am off for now, but stay tuned for your next installment of Wet Plate Wednesday! Recently while scrolling through images on eBay, I spotted this image of mother and child. It was labeled "Antique Tintype Daguerreotype Photograph of Mother & Child In Original Frame". I scratched my head a bit. Which is it? A tintype or daguerreotype? From her clothing, I suspected she was a tintype or an ambrotype. I prefer cased images to CDVs because of the level of detail. The price was affordable for a tintype and out of this world for a daguerreotype, so I bit. When she arrived in the mail, I was eager to find the answer to the mystery (I think I am easily amused or excited in the covid 19 era). She was, as I suspected, an ambrotype. The clarity and detail of the mother were very good and the blurry baby with a hint of smile around the eyes reminded me of photographs of my own children.

Unfortunately, many people do not know the differences between these types of early photography even at museums. Our local history museum was very suspicious of me when I said they had a tintype mislabeled as a daguerreotype. "How do you know? We have been told by an expert that this is a daguerreotype?" I guess the best place to start getting people to know the correct information is sharing it. I am not a photography expert, just a collector of images, but here are some definitions to help identify types of cased images. Daguerreotype - Positive image on silver. Introduced by Jacques Daguerre in 1839. Expensive and labor intensive, but very high quality images. Quickly replaced by the Ambrotype and Ferrotype in the 1850s. Although the images are durable, tarnish to the silver plate can cause irreparable damage the image. Ambrotype - Negative image on glass with black backing. Patented in the United States in 1854. Much cheaper process than the Daguerreotype. Unfortunately, the images are vulnerable in comparison to daguerreotypes and ferrotypes. Ferrotype - Popularly referred to as tintypes. Negative image on iron coated with lacquer or black paint. Invented in Ohio by Hamilton Smith in 1856. Much less expensive and more durable than Ambrotype. Ferrotypes did not require a case. In the US, the ferrotype replaced the ambrotype by the end of the American Civil War. Popularity of the ferrotype did not catch on as quickly in Europe.  Godey’s Lady’s Book April 1841 Description of Fashion Plate Fig. 1. – Dress of poux de soie ; blue shot with pink. The corsage is plain at back and half high ; the fronts also tight to the shape, but only meeting at the very waist, being sloped away in the form of a V, and trimmed with two rows of falling lace. The skirt is without garniture, save a hem of itself about a quarter of a yard in depth ; the sleeves are plain and loose, cut out on the straight way of the material ; they are not confined any where, and reach only midway of the lower arm, the buttons of the sleeves being turned up like cuffs, (see plate), in order to display a pair of under sleeves, made of fine India muslin ; these sleeves belong to a corsage, the front of which is to be seen ; it has drawings across like the sleeves, and is finished at top by a row of narrow lace edging ; deep ruffles of lace fall over the hands. The hat is of white crepe lisse and has three flowers at the side ; the strings are of crape lisse, with a very fine satin piping all round, and edged with narrow blonde. It will be perceived, that the crown of the bonnet sits so flat that it is not at all perceptible in front. Flowers underneath the bonnet. Fig. 2. – Dress of white book muslin. The corsage is precisely the same as the one just described, except, that instead of being trimmed with two falls of lace, it has two frills of muslin small plaited, and put on with a bouillon, through which a ribbon may be inserted at pleasure. This trimming is continued down the front of the skirt of the dress, the bouillon small plaited, and inserted down the centre of the front ; a glance at out plate will suffice to make this intelligible. The chemisette, appearing in fornt, is richly embroidered. The sleeves of this dress are plain at the shoulder, and the remainder nearly tight. Gauze cap trimmed with satin ribbon ; the cap is without strings to tie. Hiar in bands, brought low at the sides of the face, where it is turned up again. Fig. 3. – The corsage almost similar to that of figure 1, differing in having a ribbon run through it, (see plate). Bishop sleeves, pointed cuffs, with a cap at the top of the sleeve trimmed to correspond with the collar. Rosette and ends at the waist, coloured silk skirt, a wide flounce and heading pinked out. Bonnet of fancy lace, trimmed with lace and flowers. Fig. 4. – Dress of silk or muslin, with tight sleeves, lace waist, made of puffs and with caps on the sleeves to put on over the dress ; the waist finished with cord and tassel ; one extra wide flounce. Drawn bonnet, cottage form, trimmed with wheat and ribbon. Light fancy sash. Godey’s Lady’s Book

January, 1849 Description of the Fashion Plate. Having “distanced” all our contemporaries, it only remained for us to anticipate Nature, and we therefore present a picture of green fields and waving woodlands, even though January’s cold may be at this moment chilling the graceful forms of our lady readers. Seriously, having given all the stylish cloaks and mantillas that pleased us, and thinking by this time they had been profited by in the selection of winter wardrobes, we have exerted our taste and ingenuity in getting out a pretty spring costume, that our demoiselles may have some clue to what will be worn the ensuing season. Apart from the information conveyed, we flatter ourselves that as a picture, it adds much to the beauty of the number, and will bear preservation long after the styles it faithfully portrays shall have become antique. Figure 1st – Riding dress for the country. – Leghorn hat, with a rolled brim, the dress a full skirt of pale drab-colored cashmere, fastened up the front by a close row of very small silk buttons of the same color. A “Jack Sheppard” waist (see Lady’s Book for November) of nankeen, with a rich white linen braid embroidery on the front and sleeves. The short skirt, or basque, is trimmed in the same way as the waist, and lined with pale blue Florence silk. Plain linen collar and cuffs, and a blue ribbon neck tie. Gloves as near as possible the shade of the waist. 2d figure – Morning dress for a watering-place. – Under robe of white cambric muslin, with a border of narrow tucks and fine embroidery. Over dress of jaconet muslin, the sleeves wide and loose at the wrist. This robe has a rich border of needlework, with a scalloped edge. A belt of pale green fastened by a small gold buckle, confines it at the waist. Hat of uncut Leghorn, trimmed with pale green ribbon, and a fall of deep lace, that, thrown back over the brim, serves as a veil. The hat is designed expressly and only for the country, where it will be found very useful. Godey’s Lady’s Book

April 1861 Description of Steel Fashion-Plate for April. Fig. 1.—Child’s walking-dress of blue cashmere, with small round pelerine. The dress is braided with very narrow black velvet, and has long ends of the cashmere, braided, fastened to a belt falling at the back. Fig. 2.—Infant’s robe, elegantly embroidered en tablier; trimmed with blue rosettes; wide sash of blue ribbon, and cap trimmed to match. Fig. 3.—Nurses’ dress of brown de laine, with narrow frill at the neck. Fig. 4.—Dress of lavender-colored silk, with nine graduated flounces bound with lavender silk, relieved with black velvet stripes; sash bound with the same; body plain, trimmed with folds of the material, crossing from right to left in front; angel sleeves, trimmed with a puffing of the silk, and caught together with narrow bands. Straw-colored gloves, with two buttons, and worked with lavender-color. Bonnet of rice straw, trimmed with fuchsia-colored ribbon and Marguerites of the same color. Fig. 5.—A wine-colored silk, with three flounces bound with black velvet and a puffing at the bottom of the skirt; then three flounces graduated in their width, and a puffing put on in festoons, each festoon being caught up with a large ribbon bow and ends; body trimmed en berthé, with two ruffles and a puffing; sleeves loose, and trimmed to match the skirt. Ribbon sash, with bow and ends. Gloves worked with wine-color, to match the dress. Frill of lace round the neck. Fig. 6.—Green silk dress, having the front breadth gored, and nine very small ruffles at the bottom of the skirt; a row of buttons down the front of the dress; body plain; sleeves with caps, and trimmed at the bottom with box plaits and ruching. Point lace collar and sleeves. Leghorn bonnet, trimmed with bunches of cherries; the bonnet ribbon has also cherries worked on it. Gloves worked with green. While everyone in my house is asleep, I like to work on research projects. Currently, my catalogues are a mess. I have no idea what I have in my collections. I decided to start with my photographs. This 1850's 1/9 plate daguerreotype needed new seals, so I decided to scan her while she was open. She is so incredibly clear. I love all the little details in her bonnet, but am absolutely fascinated by her collar. Does anyone know what kind of treatment that is?

The Lady’s Book. July 1831 Philadelphia Fashions for July, 1831. First Figure.—Dress of transparent crape over a white Florence. Sleeves of blond or bobbinet, very wide and full, finished with cuffs and epaulettes of the same material as the dress. Hair in large folds and bows, with no other ornament than a white rose. Second Figure.—Dress of painted muslin. Canezon handkerchief of French worlds muslin. Grenadine scarf. Bonnet, with a round crow of white gros de nap, and a front of coloured woodlawn ; folds of wood-lawn go nearly round the crown. The trimming is of white gauze riband, edged and figured with the same colour as the wood-lawn ; each bow being finished with a knot at the bottom. The child’s dress is a frock, pantalets and cape of cambric muslin, with a narrow border of coloured braiding. A straw hat. Today we are looking at a plate from July of 1831. I am very fortunate to have in my collection several very early editions of The Lady's Book which would later become Godey's Lady's Book. In the early to mid 1830s, there are usually only 2 fashion plates per 6 month volume. Even into the 1840s, not every month has a plate and they often do not have description. Other magazines, such as the Lady's Cabinet, have four plates per month with descriptions making them a better bang for your buck if you are only interested in fashion. However, Godey's is so much more than a fashion magazine. Within its pages, you will find works from authors like Edgar Allan Poe and Nathanial Hawthorne, sheet music, architectural plans, and so many other things that make it a great place to examine cultural history.

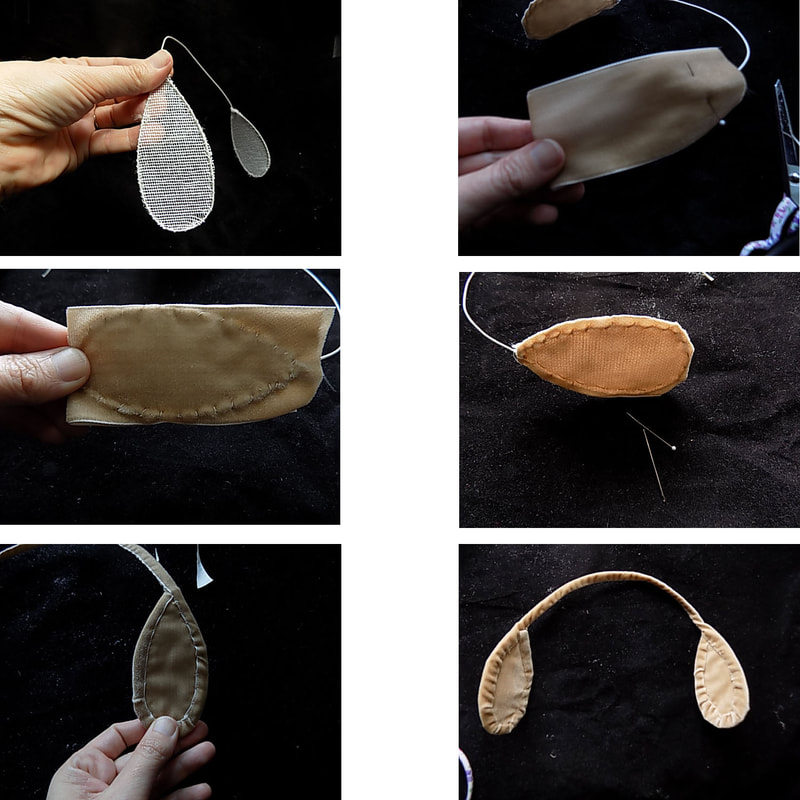

Looking at this particular plate, there are so many details to see. I love the hairstyles, the matching trim on the child's pantalets and dress, the length of the shawl, the jewelry, the tiny handbag the child holds, and so many other things. If one thing in particular really stands out, it is the bonnets (or maybe that is just because of my bonnet problem). They are crazy, almost like wearing a pizza pan on your head or the bonnet in the PBS series Sanditon that everyone freaked out about. (They were over a decade fashion forward, but guess what? that crazy thing actually was a style.) We are very fortunate that this plate actually has a description. Like many fashion plates, the colors do not match the description. The rose in the woman's hair is supposed to be white. The ribbon on the bonnet is also supposed to be white. The dress on the bonneted figure is "of painted muslin". The plate as a whole makes me want to start a new early 1830's impression. Who is with me? A base for an evening headdress is easy to create at home. The examples below are from the MET museum dating from the 1840s to the 1860s. Start with some millinery wire and buckram. Cut a teardrop shape from the buckram approximately 3" x 1 1/2". Wire around the teardrops leaving a wire section to cross the top of the head. Cover the frame with velvet to match your hair. Velvet helps the headdress cling to the hair and keep from slipping off of the head. Velvet ribbon works well. Fold the velvet in half over the tear drop. Baste the velvet to the buckram. Bind around each teardrop and across the top with coordinating velvet. Trim the teardrop sections with ribbons or flowers to taste. Hairpins at the top of each section will help attach the headdress to your properly styled hair. For kits and premade headdress bases, click here.

As many of you know, here at Timely Tresses, we love fashion plates. We love collecting them. We love investigating dates when we come across plates which we are not familiar. Over the next few weeks at least, I am determined to put beautiful things on the internet to brighten days that might not look so sunny. I hope to start a number of different series of images, the first of which is Fashion Plate Friday. This hand-colored steel engraving appeared in Godey's Lady's Book in April of 1845.

A few years ago, I found these two ambrotypes of the same young woman on eBay. The seller had them available in two different auctions. I was very fortunate to win them both. It would be such a shame for the images to be separated. The image on the left is the earlier image probably dating from 1855 or 1856. The bonnet is lower on top. The ties are shorter. Her hair is in an earlier style. The second image, from the later 1850s, shows a larger bonnet with longer ties with more emphasis moving toward the top of the brim as we move towards the 1860s. In the earlier image, the woman has her shawl pulled back showing lots of little details. We can see her collar, some jewelry, and the shape and fabric of her dress. In the second image, she appears to have dark circles under her eyes and is completely covered. Could something have happened? What differences do you see? Join the discussion on Facebook.

Choosing Your Best BudsHave you heard you can't mix flower types on a bonnet? I have and from reputable sources too. In my collection of extant bonnets, I have a bonnet with only one kind of flowers. However, I also have bonnets with mixed wreaths of flowers. Unfortunately, the vast majority of extant bonnets no longer have flowers because flowers were removed and reused. One great thing about mid 19th century research is in addition to extant garments, we have pictures. We can see real women wearing garments. Furthermore, with modern technology, we can enlarge pictures and focus in on different details. I have a lot of pictures of women in bonnets. In fact, I need all the pictures of women in bonnets. I can't just look at them on the internet. I have to buy them. If I have them in my hot little hands, I can scan or photograph them and zoom in on the parts I want to view. In looking at millinery flowers, I find some women who repeat the same flower. However, the vast majority of the photographs in my collection show mixed wreaths of flowers. So go ahead. Mix them up. They did. In preparation for a straw bonnet workshop I am teaching at the 1860's Civilian Celebration at Capon Springs in May, I have been making curtain/bavolet and facing kits. As I cut the silk, I thought "wow these look really long." I pulled out Drawn Bonnets: Examination and Construction because I knew I took detailed measurements in writing that book. I found that I had a measurement on how long the curtain would hang on the neck, but not a length measurement from point to point. So I soon found myself in a pile of originals with a measuring tape before taking my children to school. That is why I have all of these bonnets after all. I pulled 18 circa 1855-1865 bonnets that still had curtains (a lot of extant bonnets are missing curtains). The curtains I measured ranged from 16 to 28 inches in length. The average was 20". The most common measurement was 20". I looked at the longest and shortest measurements to see if that changed with bonnet style. In the group there are three very high brimmed bonnets. Two high brim bonnet curtains measured longer than 26" and the other curtain measured 17". I thought the mid 1860s bonnets with shorter points would have the shorter curtains, but that wasn't the case. They were still measuring about 20". I also wondered if there would be a difference between straw and silk. The straw bonnet curtains ranged from 16 to 27". The silk bonnets curtains ranged from 16 to 28". Most of the curtains were flat on the sides of the bonnets with the gathers or pleats concentrated at the center back with many of them being wired at the bottom edge.

I love original garments. I love fashion plates. I love reproducing the garments in them. I love patterns pulled from extant garments. I don't love ending up with the exact same garment as everyone else who made the pattern. My solution to the is problem is having a standard set of patterns that I know fit me and pulling pieces of different patterns to create different looks.

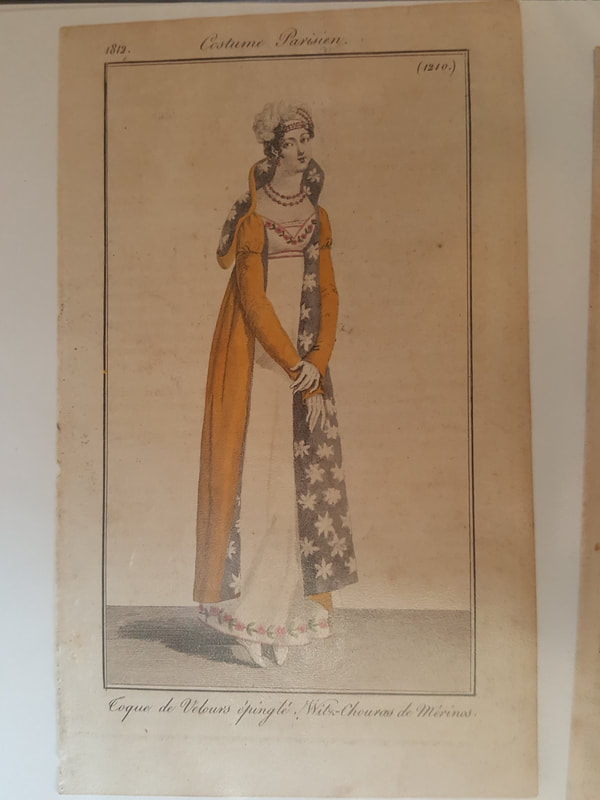

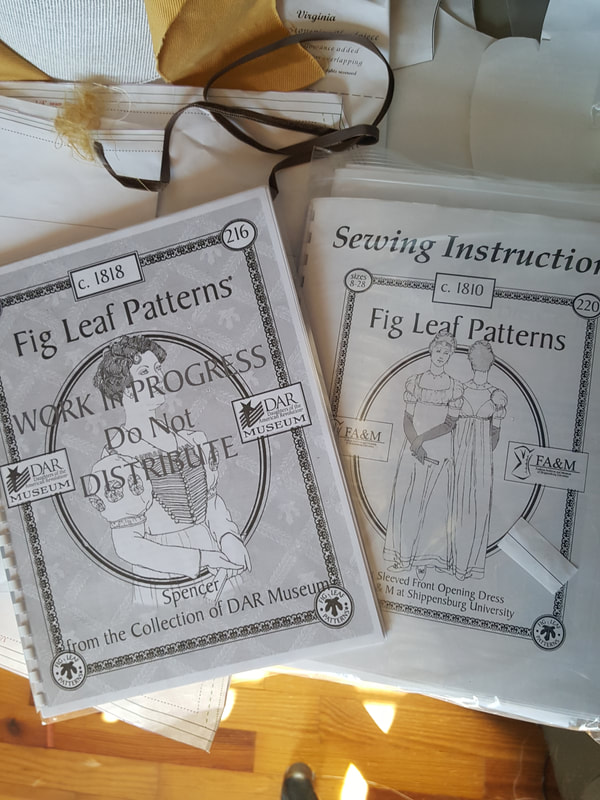

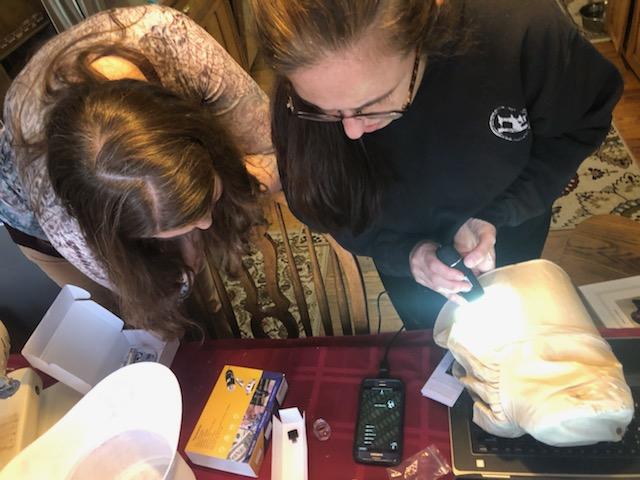

My current project is a Federal Era redingote/pelisse. I cut it out last year for the Treat of Ghent event in Camden, SC. I was then told by a well meaning friend that American women didn't wear them. I reached out to several friends in the museum field and we came to the conclusion that American women did in fact wear coats. There is a late 18 teens pelisse in the Agreeable Tyrant exhibit attributed to a Michigan woman. There is also a pelisse in the collection of the Charleston Museum. These coats were enough for me to determine that it was in fact OK for me to proceed with my pelisse. Looking through fashion plates and extant coats I decided to use a gold silk faille that I had been holding on to for years. Not my color, but extremely fashionable for Regency or Federal Era clothing. As far as style, I wanted something for late teens. I liked the renaissance style puffed sleeves on the Agreeable Tyrant pelisse. I also have a fashion plate in my collection that shows a coat in the same color, but with a crazy lining. I would have recreated the fashion plate if I could only find a silk print like the plates. I decided to settle for a gold pelisse similar in style to the two coats combined. Oh, but where to find the pattern? I had pattern 216 by Fig Leaf Patterns which almost exactly like the bodice of the Agreeable Tyrant pelisse. I decided that was the perfect place to start. Now on to the skirts! I could draft them myself, but why reinvent the wheel? I pulled out pattern 220 also by Fig Leaf Patterns to make the skirts. I used the pattern last year to make a ball gown and I liked the gored skirt which was roomy, but flat across the front (avoiding the everyone looks like they are expecting in Regency gowns look). I cut the front panels individually rather than on the fold like the pattern suggests to create the two front panels. Now here is where the coat turns into a fantasy garment. I was watching the Witcher (yes, I am a science-fiction/fantasy goofball) and loved the fur trim on Yennifer's coat. I remembered I had an old 1970's fur coat that was falling apart that she thought I could use for something rather than throw it away. I did go back to the originals and fashion plates rather than go completely off of the deep end. I found several fur trimmed pelisses in my own fashion plate collection and a fur trimmed extant in Napoleon Empire of Fashion by Cristina Barreto. (Here is the back view. I couldn't find the front view in a shareable link. ) I decided to do a fur collar, a small fur cuff, fur down the front, and around the hem. The old coat would amply supply all of this with some remaining left over for future use. Mandy and I got together today to work on bonnets. While she was here, I decided to pull out a couple of original bonnets that she hadn't seen yet. During our examination, we discussed our decision to move from single layer to double layer buckram forms. We pulled out the handy dandy microscope and compared single layer (left), double layer (center), and extant (right) buckram. The differences in the weave and density are rather obvious in the photographs. The double layer is significantly better creating a studier form. (Don't worry mid-19th century folks! Our brims for 1855-1865 are made of stiff cotton netting. Just the crowns are buckram.)

When looking at 1850's and 1860's reproduction bonnets, there is one little detail that living historians often miss: The Cap. The cap is a frill of netting or lace around the face seen in 1850's and 1860's bonnets which was a replacement of separate caps. Unfortunately, trimmings including caps have been removed from many extant bonnets making the cap seem like a little skippable detail. However, looking at antique photographs will show caps as almost universal on bonnets making them and important detail present on quality reproduction bonnets.

In this digital age many people ask me, why I collect originals rather than just viewing online. Looking at online museums, eBay, Etsy, and countless others, there seem to be endless images of antique photographs and original garments to examine. In the case of original photographs, one of the reasons is resolution. Ambrotypes, daguerreotypes, and tintypes contain a level of detail that is absolutely mind blowing. For example, this 1850's ambrotype is approximately two by three inches in size. A scan of the image allows me to look at the individual flowers in the bonnet and details in the cap that wouldn't be recognizable at the original size. Looking at the ties, one can see that they aren't hemmed, cut rather messily, have a picot edge, and are even a bit wrinkled.

When I started participating in living history, I always thought I will never do the 1820s. The twenties are too crazy. Then I took a closer look. Now, the 1820s is probably my favorite decade. Elaborate trimmings, wide bonnets at flirty angles, and oh the hair!!! If you are looking forward to 1820s 200th anniversary events, we are here to help. Last year, we released our Sophia pattern offering multiple brim options to span the 1820s. Additionally, our new and improved 1820's fashion plate book has 79 fashion plates spanning the decade to help you perfect your historic impression!

Many of you have been to my workshops on preparing feathers. I also offer prepared feathers at events, but never on the website. Well they are here. Each feather is individually curled, sewn into a bunch, and then curled again. These feather bunches add a level of sophistication and luxuriousness not often seen in historic reproductions.

In preparation for the Treaty of Ghent event in Camden, South Carolina, I decided to make a batch of Federal Era Toques. These little puffy confections can dress up a winter coat and are even appropriate to wear in the ballroom. The best part of these darlings is they are an affordable way to dress up your impression or show off some delicious millinery trimmings.

In the last couple of years, I have really slowed down as far as collecting for several reasons. First, I have a lot of bonnets and have gotten rather picky. I really don't need several of the exact same thing. Second, the bonnets I find are just too expensive and I am not finding the deals I once did. That changed recently. I found two incorrectly marked relatively inexpensive bonnets.

The first bonnet was labelled as a sunbonnet and was pointed out to me by my friend Anna Worden Bauersmith. Anna and I will point bonnets out to each other that we feel that one of us "needs." The pictures were not great, but the shape was right for mid 1840s bonnet. The seller described the bonnet as in poor condition, but for $20 plus shipping I was willing to risk it just to study the shape. I received the bonnet and opened it to find it in excellent condition for a bonnet that is almost 180 years old. It is dented, but the silk faille fabric is in very nice condition. The brim, made of both buckram and pasteboard, makes it a transitional piece from the early to mid 19th century. The second bonnet was also pointed out to me by Anna. It was labeled 1880s. A lot of bonnets are labeled 1860s when they are 1880s, but not the other way around. This bonnet has all the characteristics of a mid 1860s Empire bonnet. It has points which are not present on 1880s bonnets. It has a little flared piece under the bavolet characteristic of mid 1860's bonnets. Another super cool thing about this bonnet is the trim. First of all, I am thrilled that it still has trimming, but even more what the trimmings tell me about this bonnet. Almost all black bonnets are labeled mourning bonnets, they are not. This one is. The presence of crape and flat rather than shiny ribbons indicate that this bonnet is indeed a mid 1860s mourning bonnet. |

AuthorUsually Dannielle, sometimes Mandy Archives

January 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed