|

While everyone in my house is asleep, I like to work on research projects. Currently, my catalogues are a mess. I have no idea what I have in my collections. I decided to start with my photographs. This 1850's 1/9 plate daguerreotype needed new seals, so I decided to scan her while she was open. She is so incredibly clear. I love all the little details in her bonnet, but am absolutely fascinated by her collar. Does anyone know what kind of treatment that is?

3 Comments

The Lady’s Book. July 1831 Philadelphia Fashions for July, 1831. First Figure.—Dress of transparent crape over a white Florence. Sleeves of blond or bobbinet, very wide and full, finished with cuffs and epaulettes of the same material as the dress. Hair in large folds and bows, with no other ornament than a white rose. Second Figure.—Dress of painted muslin. Canezon handkerchief of French worlds muslin. Grenadine scarf. Bonnet, with a round crow of white gros de nap, and a front of coloured woodlawn ; folds of wood-lawn go nearly round the crown. The trimming is of white gauze riband, edged and figured with the same colour as the wood-lawn ; each bow being finished with a knot at the bottom. The child’s dress is a frock, pantalets and cape of cambric muslin, with a narrow border of coloured braiding. A straw hat. Today we are looking at a plate from July of 1831. I am very fortunate to have in my collection several very early editions of The Lady's Book which would later become Godey's Lady's Book. In the early to mid 1830s, there are usually only 2 fashion plates per 6 month volume. Even into the 1840s, not every month has a plate and they often do not have description. Other magazines, such as the Lady's Cabinet, have four plates per month with descriptions making them a better bang for your buck if you are only interested in fashion. However, Godey's is so much more than a fashion magazine. Within its pages, you will find works from authors like Edgar Allan Poe and Nathanial Hawthorne, sheet music, architectural plans, and so many other things that make it a great place to examine cultural history.

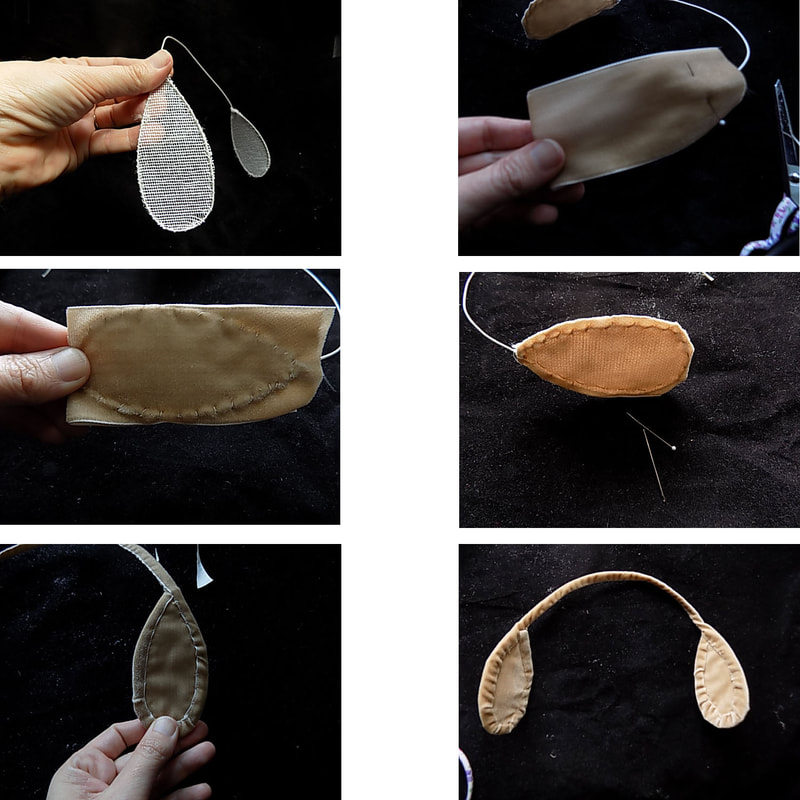

Looking at this particular plate, there are so many details to see. I love the hairstyles, the matching trim on the child's pantalets and dress, the length of the shawl, the jewelry, the tiny handbag the child holds, and so many other things. If one thing in particular really stands out, it is the bonnets (or maybe that is just because of my bonnet problem). They are crazy, almost like wearing a pizza pan on your head or the bonnet in the PBS series Sanditon that everyone freaked out about. (They were over a decade fashion forward, but guess what? that crazy thing actually was a style.) We are very fortunate that this plate actually has a description. Like many fashion plates, the colors do not match the description. The rose in the woman's hair is supposed to be white. The ribbon on the bonnet is also supposed to be white. The dress on the bonneted figure is "of painted muslin". The plate as a whole makes me want to start a new early 1830's impression. Who is with me? A base for an evening headdress is easy to create at home. The examples below are from the MET museum dating from the 1840s to the 1860s. Start with some millinery wire and buckram. Cut a teardrop shape from the buckram approximately 3" x 1 1/2". Wire around the teardrops leaving a wire section to cross the top of the head. Cover the frame with velvet to match your hair. Velvet helps the headdress cling to the hair and keep from slipping off of the head. Velvet ribbon works well. Fold the velvet in half over the tear drop. Baste the velvet to the buckram. Bind around each teardrop and across the top with coordinating velvet. Trim the teardrop sections with ribbons or flowers to taste. Hairpins at the top of each section will help attach the headdress to your properly styled hair. For kits and premade headdress bases, click here.

As many of you know, here at Timely Tresses, we love fashion plates. We love collecting them. We love investigating dates when we come across plates which we are not familiar. Over the next few weeks at least, I am determined to put beautiful things on the internet to brighten days that might not look so sunny. I hope to start a number of different series of images, the first of which is Fashion Plate Friday. This hand-colored steel engraving appeared in Godey's Lady's Book in April of 1845.

A few years ago, I found these two ambrotypes of the same young woman on eBay. The seller had them available in two different auctions. I was very fortunate to win them both. It would be such a shame for the images to be separated. The image on the left is the earlier image probably dating from 1855 or 1856. The bonnet is lower on top. The ties are shorter. Her hair is in an earlier style. The second image, from the later 1850s, shows a larger bonnet with longer ties with more emphasis moving toward the top of the brim as we move towards the 1860s. In the earlier image, the woman has her shawl pulled back showing lots of little details. We can see her collar, some jewelry, and the shape and fabric of her dress. In the second image, she appears to have dark circles under her eyes and is completely covered. Could something have happened? What differences do you see? Join the discussion on Facebook.

Choosing Your Best BudsHave you heard you can't mix flower types on a bonnet? I have and from reputable sources too. In my collection of extant bonnets, I have a bonnet with only one kind of flowers. However, I also have bonnets with mixed wreaths of flowers. Unfortunately, the vast majority of extant bonnets no longer have flowers because flowers were removed and reused. One great thing about mid 19th century research is in addition to extant garments, we have pictures. We can see real women wearing garments. Furthermore, with modern technology, we can enlarge pictures and focus in on different details. I have a lot of pictures of women in bonnets. In fact, I need all the pictures of women in bonnets. I can't just look at them on the internet. I have to buy them. If I have them in my hot little hands, I can scan or photograph them and zoom in on the parts I want to view. In looking at millinery flowers, I find some women who repeat the same flower. However, the vast majority of the photographs in my collection show mixed wreaths of flowers. So go ahead. Mix them up. They did. In preparation for a straw bonnet workshop I am teaching at the 1860's Civilian Celebration at Capon Springs in May, I have been making curtain/bavolet and facing kits. As I cut the silk, I thought "wow these look really long." I pulled out Drawn Bonnets: Examination and Construction because I knew I took detailed measurements in writing that book. I found that I had a measurement on how long the curtain would hang on the neck, but not a length measurement from point to point. So I soon found myself in a pile of originals with a measuring tape before taking my children to school. That is why I have all of these bonnets after all. I pulled 18 circa 1855-1865 bonnets that still had curtains (a lot of extant bonnets are missing curtains). The curtains I measured ranged from 16 to 28 inches in length. The average was 20". The most common measurement was 20". I looked at the longest and shortest measurements to see if that changed with bonnet style. In the group there are three very high brimmed bonnets. Two high brim bonnet curtains measured longer than 26" and the other curtain measured 17". I thought the mid 1860s bonnets with shorter points would have the shorter curtains, but that wasn't the case. They were still measuring about 20". I also wondered if there would be a difference between straw and silk. The straw bonnet curtains ranged from 16 to 27". The silk bonnets curtains ranged from 16 to 28". Most of the curtains were flat on the sides of the bonnets with the gathers or pleats concentrated at the center back with many of them being wired at the bottom edge.

|

AuthorUsually Dannielle, sometimes Mandy Archives

January 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed